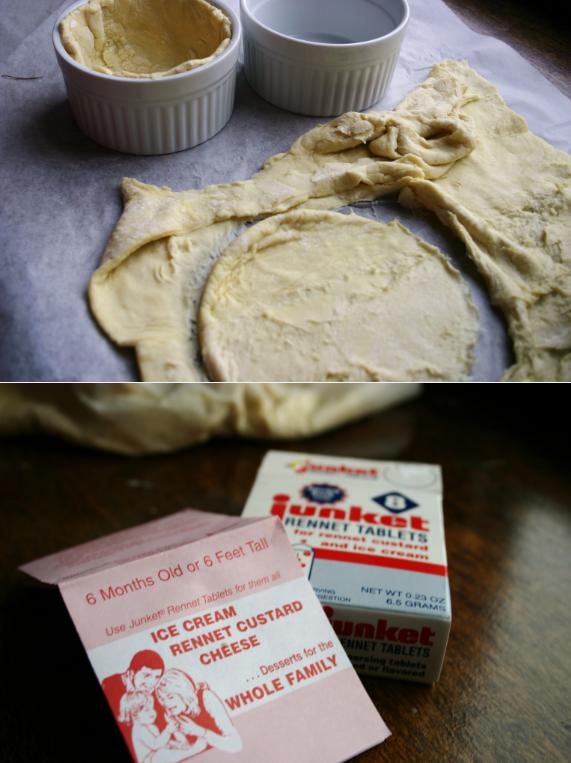

Note: I’ve never had a guest post on P&S belore, but when Aimee Gasston told me about the unpublished recipes she found in Katherine Mansfield’s papers, I couldn’t wait to have her share one here. Plus, I’ll clearly take any opportunity to trot out my ramekins (I’m a sucker for individual-size desserts). Enjoy, and many thanks to Aimee.

Another Note: If you’re reading this via Google Reader, there are alternatives to get P&S updates after Reader shuts down tomorrow. Plus, you can always find what’s up on Facebook. Okay, back to regularly scheduled programming.

It’s lucky that Katherine Mansfield, maybe the key innovator of modernist short fiction, had such a hearty appetite, without which her prose would be far less rich. Virginia Woolf described Mansfield as having the finest senses of her generation – so when I heard about newly discovered food-related material of hers acquired by the Alexander Turnbull Library in Wellington, New Zealand, I couldn’t wait to get a look at it.

Plump as a child, Mansfield would be made gaunt by tuberculosis in adulthood, but her hunger for worldly pleasures remained constant throughout her truncated life. Her personal writing is full of daydreams involving food, which she vividly described in letters and journals as she traveled Europe in search of health.

Switzerland was a particular disappointment, as she wrote in a letter to the artist Anne Estelle Rice in 1921: “Curse them. And the FOOD. It’s got no nerves. You know what I mean? It seems to lie down and wait for you; the very steaks are meek. […] As to the purée de pommes de terre, you feel inclined to call it ‘uncle.'”

Despite her love of eating, cooking wasn’t the most pressing of Mansfield’s priorities due to her poor health and a fierce dedication to her work. In her excellent biography A Secret Life, Claire Tomalin describes Mansfield and her husband John Middleton Murry’s juvenile culinary tendencies: “Like children, they lived mostly on the junk food of the day, meat pies and the cheapest possible restaurants; Katherine had no time or wish to cook.”

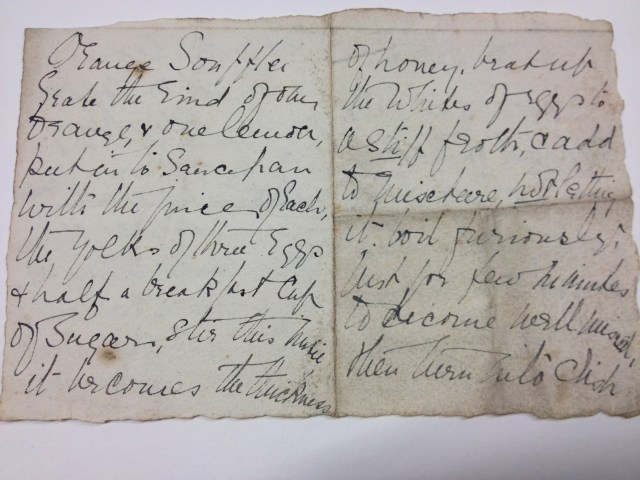

Instead, Mansfield’s cooking would take place largely on the page. Besides the spirited culinary rhymes that she penned amid her account books (including an unpublished poem called “An Escapade Undertaken by a Green Raspberry and a Kidney Bean”), her short fiction was always embroiled with the messy materiality of life, with prose you cannot only see, hear, touch and smell, but really taste.

* * *

Continue reading “Katherine Mansfield: Orange Soufflé with Sherry Syrup”