When I got married, my Louisiana native in-laws gave me a new cookbook for my collection: Talk about Good!, a production of the Junior League of Lafayette. The giant spiral-bound tome was a primer on Cajun cooking, bringing together hundreds of recipes passed down by generations of members and their families. Now, when the instructions for any conceivable dish are just a Google search away, community-sourced cookbooks like these are a reminder that finding the perfect recipe wasn’t always so simple—and that good friends were an essential resource in the hunt.

Thornton Wilder had a particularly fruitful recipe resource: his friends Alice B. Toklas and Gertrude Stein. Toklas’ most enduring cooking legacy may be her recipe for pot brownies (which Wilder called “the publicity stunt of the year”), but she shared many more recipes directly with her friends, well before deciding to publish a book of them.

Thornton didn’t cook those recipes himself; that role belonged to his sister Isabel, with whom he lived for much of his life. (Isabel’s responsibilities weren’t limited to cooking. At one particular dinner party, Alice fried chicken and asked Thornton whether he wanted light or dark meat; he turned to Isabel and asked earnestly, “Which is it I prefer?”). But both Wilders loved to eat and were willing recipe-testers for Toklas, hosting her at their Chicago apartment and ordering groceries in.

Even more useful for his friends, Thornton was an international sharer of recipes, serving as go-between for his contacts in Europe and his family and friends in the United States. He brought Isabel recipe books from France (“Isabel was screaming with pleasure over the pastry-dessert book,” he wrote to Stein) and shared Toklas’ recipes with curious acquaintances in the U.S. (“They look mighty elaborate to me; but good,” he editorialized.) Even his lawyer’s wife tried to get in on the action: After receiving a long letter from Wilder, filled with details about dinners with French luminaries like Coco Chanel and Elsa Schiaparelli, his lawyer responded tersely, “Anna is more interested in recipes.”

The Wilders sent recipes to Toklas too, but theirs were more, shall we say, focused: They were all about ice cream. “Alice has just had a charming letter from Isabel and all evening she was crowing over ice cream recipes,” Stein wrote to Thornton. Ice cream was the dessert for the Wilders over the decades: It appears throughout Thornton’s letters, whether as a treat for himself as a student in Italy (“I passed an American soldier … I ran back and spoke to him, inviting him to have an ice-cream with me”) or for his sisters during a hot summer on Long Island (“Passing through Amityville village get Charlotte a half-pint of vanilla ice-cream.”)

Toklas eventually published several of her own ice cream recipes in her famous book, perhaps inspired by those sent by Isabel. The recipes that Stein references in that have not been found; we also don’t have any of Thornton’s reactions to testing Toklas’ ice cream efforts. But we do have the words of Sabina, the dominant presence in his Pulitzer Prize-winning play The Skin of Our Teeth, whose philosophy I’m officially adopting when it comes to dessert: “My advice to you is not to inquire into why or whither, but just enjoy your ice cream while it’s on your plate.”

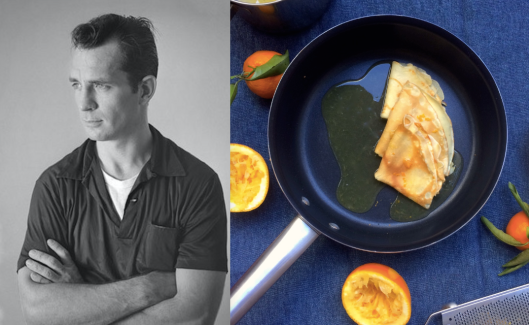

Although Toklas presents six ice cream recipes in her book, the nougat flavor stood out to me; made with honey instead of sugar and packed with pistachios and almonds, it’s like nougat candy in frozen form. The toasted nuts also reminded me of a compliment Thornton paid to Gertrude Stein in a letter, calling her “A wonder … a seer … you’re my Toasted ice-cream.” This was a reference to one of Stein’s own poems, but the line’s meaning evolved among this recipe-focused circle of friends, in which comparison to dessert was the highest praise.

Adapted from The Alice B. Toklas Cook Book

- 1 1/2 cups heavy cream

- 1 1/2 cups whole milk

- 6 egg yolks

- 2/3 cup honey

- 2 teaspoons orange flower water or Cointreau

- 1/4 cup raw almonds

- 1/4 cup raw shelled pistachios

- Heat cream and milk in a small heavy saucepan over medium-low heat. Bring to a boil, stirring occasionally so the bottom of the pan doesn’t scorch.

- As the mixture comes to a boil, whisk egg yolks in a medium bowl until frothy and lighter in color.

- When the milk is just boiling, pour 1/4 of the liquid into the egg yolks, whisking constantly, then pour the egg yolk mixture into the saucepan. Continue whisking constantly over medium-low heat until the mixture has thickened slightly and coats the back of a spoon. Remove from heat.

- Stir honey and orange flower water into the milk mixture until completely dissolved. Let cool slightly, then cover and refrigerate overnight.

- The next day, preheat oven to 350 degrees F. Spread almonds and pistachios on a baking sheet; toast 5 to 8 minutes, watching carefully, until fragrant but not burned. Set aside to cool completely, then coarsely chop nuts.

- Place ice cream base in an ice cream maker and churn according to manufacturer’s instructions; when nearly done, add the toasted nuts. (Alternatively, just pour the base into a cold-safe container, stir in the nuts, and pop in the freezer; Toklas’ step says simply, “Freeze.”)