Imagine this: It’s a Sunday night, the end of a long weekend full of gift shopping, cookie baking, and fun-but-exhausting holiday merrymaking. You can’t possibly cook now, you decide, and turn to your trusty takeout-menu drawer. What are you in the mood for, though? Thai? Italian? Indian? Ethiopian?

If there’s one thing I bet you didn’t say, it’s “British.” Despite the U.K.’s recent restaurant renaissance, its meals have been a culinary punchline for nearly a century, ever since World War I hobbled the country’s food culture. George Orwell summed up its characteristics rather bluntly: “simple, rather heavy, perhaps slightly barbarous.”

Orwell was obviously never one to hide his feelings about food; his travel writings slam chefs everywhere from France to Burma. You’d think he’d be a little kinder to his home cuisine, but he savages everything from fish and chips (“definitely nasty, and has been an enemy of home cookery”) to rice puddings (“the kind of thing that one would prefer to pass over in silence”) to pretty much any kind of vegetable (“usually smothered in a tasteless white sauce”).

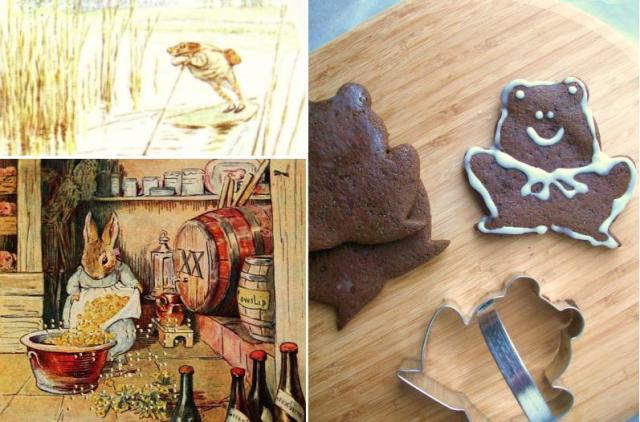

But Orwell did reserve some praise for what was, in his mind, Britain’s crowning culinary glory: “sweet dishes and confectionery—cakes, puddings, jams, biscuits.” Best of all were the Christmas treats: plum pudding, and treacle tart, “a delicious dish … hardly to be found in other countries.”

So how could a food lover like Orwell explain the U.K.’s mediocre showing in the kitchen? As he tells it, it’s because the best English cooking isn’t at a charming bistro or fancy restaurant, but is made at home, where foreigners don’t have access. That may be bad news for tourists—but it’s a moment for home cooks to shine. When we’re baking scones or Yorkshire puddings, Orwell says, we can be chefs of our own making.

* * *