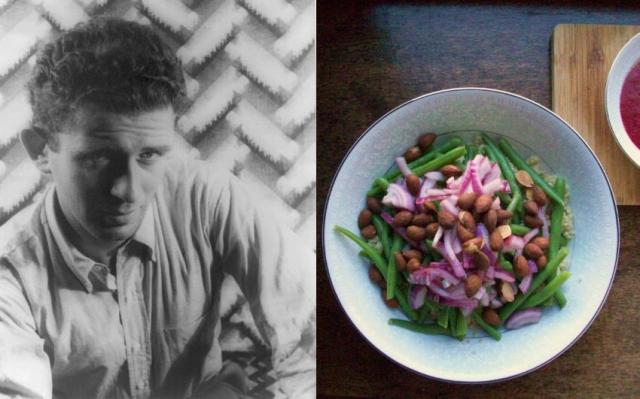

There’s a scene in Ralph Ellison’s The Invisible Man that has become one of the most famous food passages in history. The unnamed narrator, passing a sweet-potato vendor on the road, is transported back to his childhood in the South, happily recalling meals of fried chicken and chitterlings – foods that soon became too racially charged for him to enjoy. But in this moment, the narrator is changed: He gets three orders of potato, newly determined to eat what he likes without shame. “I yam what I am,” he shouts, transformed (and if your mind went straight to Popeye, just remember what a dramatic effect food had on him).

Food unexpectedly changed the course of Ellison’s life: When he started studying music at the Tuskegee Institute, he also began working long hours in the dining hall, in order to pay off his tuition. You could find him on the early shift – 5 a.m. to 1 p.m. – baking cornbread and pouring bowls of molasses for the breakfast service. And after graduation, it was cooking – not music – that landed Ellison a job. Failing to score a coveted spot as a trumpeter in a military band, he instead found work as a cook on a Liberty ship, turning out versions of the Southern staples he learned at Tuskegee: cornbread, biscuits and fried pies.

It wasn’t until Ellison began traveling abroad, away from the Southern dishes that had defined his early years, that he realized how they had worked their way into his being. Living in Rome in 1956, Ellison wrote to his friend and fellow writer Albert Murray, “I got no way to get any corn bread … no sweet potatoes or yellow yams, a biscuit is unheard of – they think it means a cookie in this town – and their greens don’t taste like greens.”

Today fried chicken and stewed greens have gained gourmet cred – collard green risotto is totally a thing – but there will always be foods that feature guilt as a main ingredient. The phrase “you are what you eat” has become a grim warning, baking shame into things that ought to be enjoyed in moderation. We focus so much on the physical effects of our diet, it’s easy to forget that food can change us in other ways – ones that don’t involve calories or celery sticks but instead affect our minds and hearts: sweet potatoes for comfort, ice cream for renewal, chocolate for joy.

* * *