Although it’s conspicuously absent from biology classes and science textbooks, I’m convinced that certain humans (myself included) have developed a rare but necessary extension of the digestive system: the “dessert stomach.” How else to explain our ability to be simultaneously completely full of dinner, but so ready for the final course? Friends with actual medical training tell me it’s all psychological, but I’m going with the two-stomach theory.

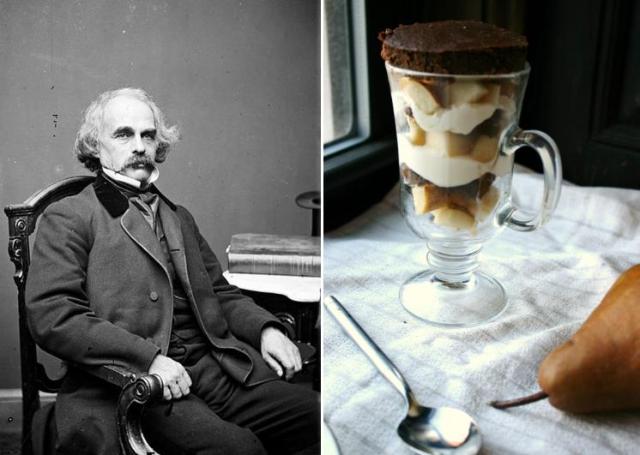

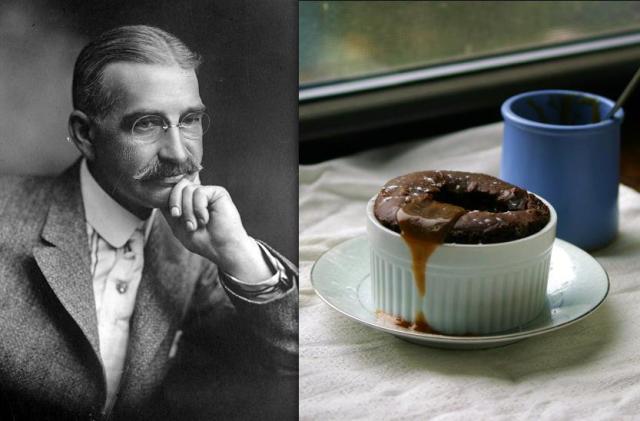

After all, the evidence goes back hundreds of years, to the New England table of Nathaniel Hawthorne. When you look at the dinner party guest lists now, they read like a survey of American literature—Emerson, Thoreau and a young Louisa May Alcott might be spotted, digging in—but the food was just as important as the company. “Should we be the more ethereal, if we did not eat?” he wondered in a letter. “I have a most human and earthly appetite.”

Even after those elaborate meals, though, Hawthorne could always find a little extra room when the main courses were cleared. Writing to his son after a particularly overwhelming feast, he admitted, “I had hardly any appetite left.” Nevertheless, “I did manage to eat some currant pudding, and a Banbury cake, and a Victoria cake, and a slice of beautiful Spanish musk-melon, and some plums.” If Hawthorne came to your Thanksgiving, he’d be the guy “testing” every kind of pie on offer (and don’t forget the ice cream).

Fruit was a frequent after-dinner treat, and Hawthorne doted on the orchards on his land (“What is a garden without its currant-bushes and fruit-trees?” he wrote). But, as anyone with a dessert stomach can attest, fruit alone isn’t nearly enough. After his daily walk through the grounds, Hawthorne would eat “a pint bowl of thick chocolate (not cocoa, but the old-fashioned chocolate) crumbed full of bread.” When fruit was in season, he’d add it to the mix—a stealth move to combine two desserts in one.

Continue reading “Nathaniel Hawthorne: Chocolate Bread Pudding Trifles”