I have always been semi-mortified about special requests in restaurants. Meg Ryan’s orders in When Harry Met Sally still fill me with third-party embarrassment. When I was in high school, my friends and I decided, instead of going to junior prom, we’d spend our ticket money on a fancy dinner in San Francisco instead. I anticipated it for weeks, poring over the menu in advance like it was some kind of ancient codex. After much deliberation, I picked the black pepper-crusted tuna steak—which, of course, arrived raw.

What to do? Amazingly (this being California in the 90s), I hadn’t yet eaten raw fish and wasn’t planning to start then. But, determined to be accommodating I picked at the seared edges of the tuna until a friend noticed, rolled her eyes, and asked our waiter to re-fire it. I watched him parade the plate back to the kitchen, as if announcing to the room, “That girl in the corner table is so uncultured, she didn’t know tuna is served rare, and we are all paying the price.”

My tolerance for special requests has improved since then (It helps that I’m no longer in high school, when even the wrong nail polish was the apex of embarrassment). And whatever I order, I know it will never compare to the culinary demands of the Marquis de Sade, who showed as much disregard for dining conventions as he did for sexual ones—that is, pretty much none whatsoever.

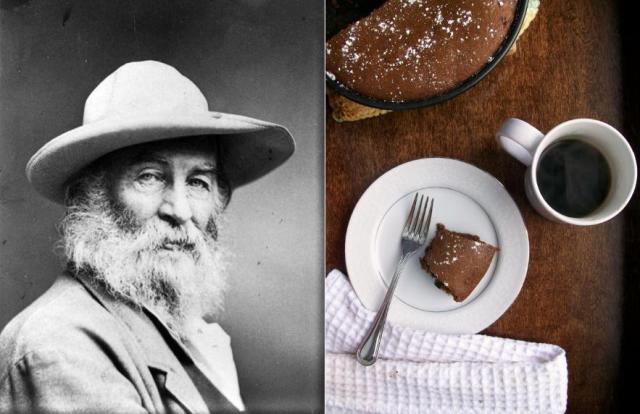

For one thing, if I were in prison, I assume that I wouldn’t have a lot of input about the food; you get what you get. Not so the Marquis. In one of his many jail stints, he counseled the chef of the Bastille about the daily menu: it had to include a custard (vanilla or coffee flavored only), baked apples, and “an excellent soup (I will not repeat this adjective; soups must always be excellent.” Try this today, and I bet you’d get a big fat of soup in your face. It would not be the excellent kind, either.

I also admit that I’ve never once ordered cookies shaped to specific dimensions. The Marquis was all over this one. His requests to the Bastille are charming compared to the letters he wrote his wife, Renee, from prison, which listed his extensive food needs, including biscuits “six inches long by four inches wide and two inches high.” He was not only particular about his sweets; his appetite for them was insatiable. Another letter to Renee asked for “four dozen meringues; two dozen sponge cakes (large); four dozen chocolate pastille candies, vanillaed, and not that infamous rubbish you sent me in the way of sweets last time.”

And woe unto the person who forgets the chocolate. “The next time you send me a package … try to have some trustworthy person there to see for themselves that some chocolate is put inside,” he snarked. He may have been a libertine in the bedroom, but in the dining room with the Marquis, you don’t fool around.

* * *

Continue reading “Marquis de Sade: Molten Chocolate Espresso Cake with Pomegranate”