Two months ago, if you had asked me to describe Willa Cather, I would have pictured her writing in the middle of the Nebraska farmland, surrounded by as many sheaves of paper as sheaves of wheat. I didn’t realize that, when she was 23, Cather left the Great Plains for the big city; she moved to Pittsburgh and then to New York, where she lived for the rest of her life. She didn’t publish her first novel until 16 years after the move, when Fifth Avenue must have been just as familiar as the farm.

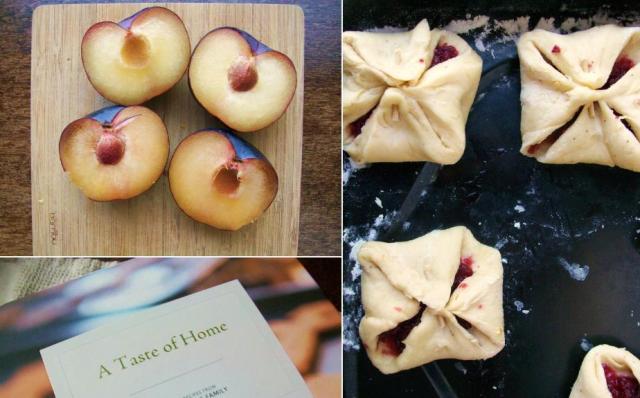

It’s no wonder, then, that food played such a major role in Cather’s writings: She needed it to bring her back to life on the frontier. With their incredible power to conjure up a time and place, food memories are some of the strongest associations around. More than anything else about a trip, I remember the meals: crabs in Baltimore, étouffée in New Orleans, pain au chocolat in Paris. When I left home in California for the unknowns of the East Coast, my mom sent me off with a bound compilation of our family’s favorite recipes. Seven years later, in my New York kitchen, I still flip it open when deciding what to make for dinner. It’s one of the best gifts I’ve ever gotten.

In Nebraska, Cather drew her cooking inspiration from Annie Pavelka, a Bohemian immigrant to the town of Red Cloud whose life (and food) would serve as the basis for My Ántonia. In her own New York kitchen, hundreds of miles from home, I imagine Cather consulting her recipes and rolling out her pastry dough like Annie did, mentally recreating the pioneer communities of her childhood.

* * *