Thinking of Dickensian food conjures up two extremes – the stuffed goose and figgy pudding feast of A Christmas Carol and the sad gruel rations of Oliver Twist. During Dickens’ 200th birthday celebrations this month, there was a lot of talk of the former. Nobody seemed as excited about the gruel, but there are plenty of resources to help you make an authentic Victorian version that actually sounds kind of great (Favorite BBC quote: “We were hoping he’d make it far more disgusting.”)

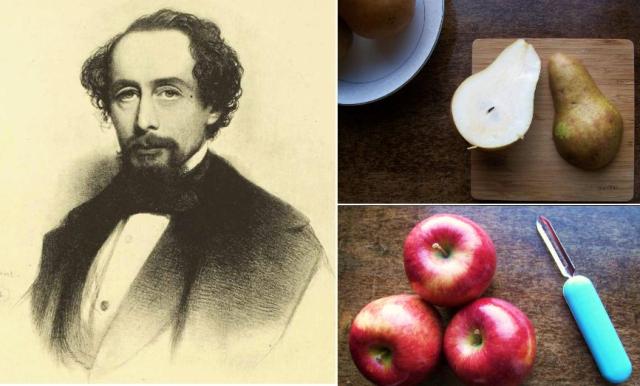

Given the fame that Dickens achieved in his lifetime, he didn’t have to beg for second helpings. But one of his favorite dishes, baked apples, was quite simple, not to mention practical: He swore by their ability to prevent seasickness.

Dickens became a baked apple convert while sailing to Boston in 1867. They were served at every meal during the Atlantic crossing, and he always helped himself. “I am confident that they did wonders, not only at the time, but in stopping the imaginary pitching and rolling after the voyage is over,” he wrote to his sister-in-law, Georgina Hogarth.

The magical apple diet clearly made an impression, and in 1881 Charles Dickens Jr. dedicated an entire cookery column to them in Household Words, a revived version of his father’s weekly magazine. Apples were getting cheaper and were beginning to be imported from abroad, so baked apples could be made by anyone, anytime. Perhaps thinking of his father, Dickens Jr. stressed the health benefits of the fruit. “It is unnecessary to say how valuable apples are as an article of diet.” Turns out, Dickens had been on the edge of a trend: The earliest version of our famous “An apple a day” saying was first published in Wales in 1866, just a year before his trip to the States.

* * *