To paraphrase Freud, sometimes a candy bar is just a candy bar. But a good one often takes on greater meaning: as a motivator, a mood-changer and, in my kindergarten class, a valuable form of currency. Trading candy at lunch seemed to determine the whole school’s social hierarchy—and nothing commanded a higher price than a Three Musketeers. Something about that weirdly aerated filling and the sweet-on-sweet combination of chocolate and nougat made our sugar-driven hearts race and sent the bids soaring.

But for Kurt Vonnegut, a world away from the playground, candy bars became something even more valuable: a reminder of home, when it never seemed further away. Part of the Allied invasion of France during WWII, Vonnegut’s regiment was captured by German forces. For six months, he and his fellow soldiers dreamed about their lives before the war—and the food they would eat if they ever returned.

Thanksgiving turkey was the most popular topic of culinary conversation among the other men, but Vonnegut had a different focus. “[He] obsessed about candy bars,” his biographer Carl Shields wrote in And So It Goes. “He swore he was going to eat every kind ever made when he got home—Almond Joy, Milky Way, PayDay, Hershey’s, Clark Bar—and loved to talk about what it would be like with his mouth stuffed.”

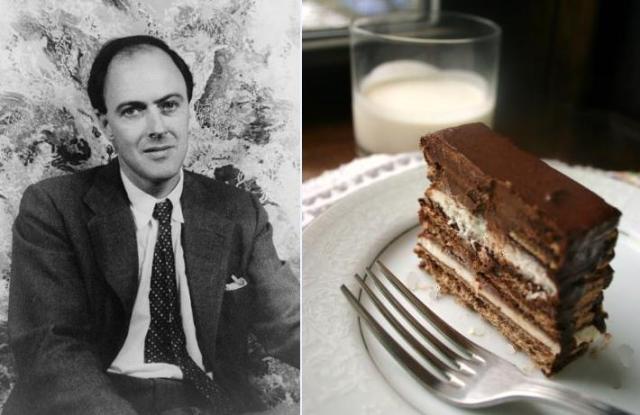

Three Musketeers, however, would take a special place in Vonnegut’s memories, and his fiction. In Slaughterhouse Five, the novel most directly inspired by his time as a prisoner of war, the candy bar pops up by name several times. And the name he gives his trio of central characters? The Three Musketeers.

Even years later, Vonnegut’s childlike devotion to sweets persisted; instead of offering visitors coffee, the default drink of writers everywhere, he’d suggest hot chocolate. And although he paired his nightly meals with two more adult pursuits—a glass of Scotch and water, jazz—his preferred recipes were equally simple, favorites of the kindergarten set that would have been a hot commodity on my childhood playground. His daughter, Edie, remembers the day he asked her for a recipe he particularly liked, “the one where the cheese melts.” It was grilled cheese.

Continue reading “Kurt Vonnegut: Spiked Three Musketeers Bars”