One hundred years ago, D.H. Lawrence was awaiting the publication of what would become his most famous (and most controversial) novel. Sons and Lovers celebrates its centennial this May—but in the weeks leading up to its release, Lawrence’s thoughts were elsewhere, in a little house across the Alps: “I want to go back to Italy,” he wrote.

Lawrence made his first trip to Italy while working on Sons and Lovers, and he felt an immediate connection. “I think I shall be happy there, and do some good work,” he said in 1912, just before settling near Lago di Garda, a few miles from Verona. Several months later, his writing was already moving along. “I do my novel well, I’m sure. It’s half done.”

But when taking a break from his desk, Lawrence was at work in the kitchen, which he praised in letters home. “There’s a great open fireplace, then two little things called fornelli – charcoal braziers – and we’ve got lots of lovely copper pans, so bright. Then I light the fornello and we cook. It’s an unending joy.” He found beauty in the smallest act of cooking—he loved his pots so much, he made sketches of them. “Everything is just red earthenware, roughly glazed, and one can cook in them beautifully.”

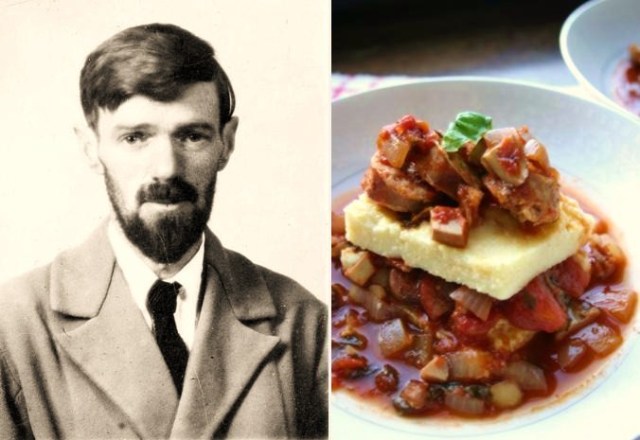

For Lawrence, Italian cuisine meant a chance to experiment with ingredients of all kinds, from the quotidian to the obscure. “We eat spaghetti and risotto and so on all of our own making,” he wrote. “We eat quantities of soup … midday polenta made of maize flour boiled to a stiff porridge that one cuts in slices with a string … queer vegetables – cardi – like thistle stalks, very good – and heaps of fresh sardines.” He frowned upon the tendency of the locals to use too much oil, but had certain indulgences of his own: “Maggi and I grate pounds of cheese,” he admitted.

If we’re lucky, we discover for ourselves what Lawrence found in Italy: that place that inspires all our creative pursuits, whether it’s at the desk or at the stove. The freedom and adventure he felt there, through, dissipated when he left Italy to go north. “I have suffered from the tightness, the domesticity of Germany. It is our domesticity which leads to our conformity, which chokes us.” Little did he know how non-conformist his new novel would be seen—a little reminder of Italy that lingered there.

* * *