Whenever I’m trying to remember something important—a due date, a birthday, the name of a friend’s new baby (oops!)—I’m always amazed by the random information my brain has quietly absorbed instead, without my knowledge. Most, to my chagrin, is completely useless: ’90s song lyrics, all the presidents in order, the name of the cat from Sabrina, the Teenage Witch. But also, without knowing how or when it happened, I unexpectedly learned to cook.

Between all the poetry, philosophy, and cultural theories, Friedrich Nietzsche’s brain wouldn’t seem to have much space for cooking skills either. Food in general often gave him more trouble than pleasure. Suffering from digestion problems, he hopped around Europe, from the French Riviera to the Italian coast, hoping the climate would restore his health. He avoided restaurants, where, he complained, “one is made accustomed to ‘overfeeding’; that is why I no longer like to eat in them.”

Yet, over the years, Nietzsche absorbed a love of cooking by learning the same way I did: through those around him. In Genoa, his landlady taught him to fry artichokes and whisk eggs for torta di carciofi, the local specialty. In Sorrento, in a villa surrounded by lemon trees, his housemaid showed him her secret to a perfect risotto, lovingly ladling out the stock as she stirred. Studying the techniques of his Italian housekeepers, Nietzsche was eager to become a teacher himself. He wrote to his mother: “I shall teach you later how to cook risotto—I know now.”

Nietzsche would later revise his opinion of restaurants, becoming a regular at several neighborhood trattorias, but he always reserved special praise for those dishes he learned himself; game recognize game. In a letter from Turin, he detailed his regular order: “minestra or risotto, a good portion of meat, vegetable and bread—all good … I eat here with the serenest disposition of soul and stomach.”

For most of us, cooking doesn’t happen intentionally; we don’t crack open a book to “Chapter 1: Let’s Talk About Knife Skills.” Instead, the path to the kitchen unwinds slowly, over a lifetime: “helping” sift the flour for a batch of cookie dough, learning to cut an onion without catching your fingers, trying to perfect the swirl on top of a meringue pie. It’s hard to remember each step we took. Instead it’s the guides we remember—be it a mother, grandmother, father or kindly landlady—for leading us along the way.

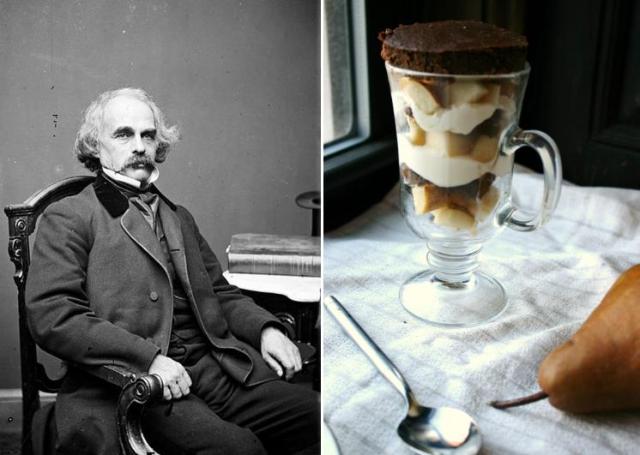

Continue reading “Friedrich Nietzsche: Lemon Risotto with Asparagus and Mint”