Last week, when Alice Munro found out she had won the Nobel Prize in literature, she was in bed. The prize committee had tried to reach her earlier by phone but ended up just leaving a voicemail, so it was Munro’s daughter who, hearing the announcement, ran to wake up her mom. That somehow seems fitting for Munro, whose stories revolve around intimate moments of domesticity. If Hemingway is a moveable feast, Munro is breakfast in bed.

Her writing is not only steeped in the household world; it also was created there. Munro’s desk is her dining room table, where she’s penned most of her work over the past few decades. As her interviewer at The Paris Review notes, “The dining room is lined floor to ceiling with books; on one side a small table holds a manual typewriter.” When she cooks in the neighboring kitchen, her work is never far away. Is it any wonder the two are connected in her stories, as in life?

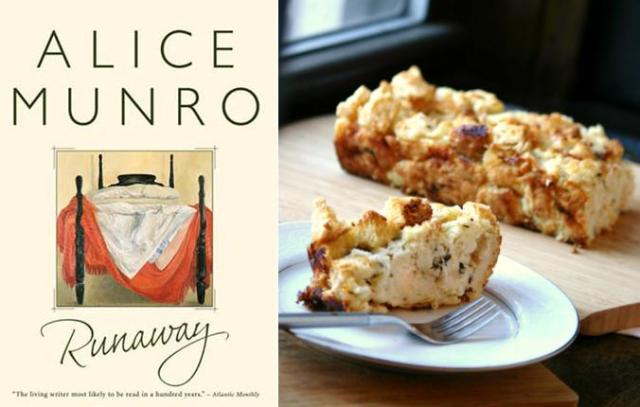

Besides writing, cooking was the other constant in Munro’s own domestic drama. In her mostly autobiographical collection The View from Castle Rock, she recalls packing her father’s lunch in the morning, a regular chore: “three thick sandwiches of fried meat and ketchup. The meat was cottage roll ends or baloney, the cheapest meat you could buy.” Later, when she was married, Munro’s stories would continue to take a back seat to food prep. She told the Review, “I would write until everybody came home for lunch and then after they went back, probably till about two-thirty, and then I would have a quick cup of coffee and start doing the housework.”

Although Munro still cooks (one of her interviewers watched her prepare a meal, which made ample use of the Canadian countryside’s fresh herbs), she now often chooses to leave the kitchen to others. She regularly asks reporters to meet at her favorite restaurant in the nearby town of Gogerich, Ontario—Bailey’s Fine Dining—where she has a usual table (corner) and a usual drink (white wine, sauvignon blanc preferred, multiple pours encouraged).

Until just a few days before the award announcement, Haruki Murakami, known for his hulking postmodern novels, was said to be the front-runner for the Nobel. It’s hard to imagine a writer further than Munro. Her subjects are often described as “quiet” or “domestic” and (given that they’re short stories) “small.”

Munro herself sometimes doubted their impact; she told the New Yorker last year, “For years and years I thought that stories were just practice, till I got time to write a novel.” But the major recognition of her work helps us all remember what a “small” story can do—how an intimate revelation at the dining room table can hold as much truth as an epic; how a perfect fried baloney sandwich can sometimes hit the spot more than any six-course meal.